Further Examples

Horizontal Motion

When you accelerate in a car you feel shoved backward into the seat. Really what's happening is the seat is shoving you in the back, but we can't tell the difference between the two descriptions. What I mean by that is that there really is no difference between the sensation of gravity and the sensation of acceleration. That's why accelerating in some direction will effectively change the way gravity seems to behave.

Suppose you have a cup of coffee on the dashboard of your car when a traffic light turns green and you accelerate(bad idea). Naturally it'd fly toward the rear of the car. Why?

In light of prior chapter conversations, friction between the cup and dashboard was apparently not enough to allow it to keep pace accelerating with the vehicle. In light of our present conversation, we can see it as a change in effective gravitation. If you are accelerating in the x-direction at 5m/s2, and gravity is 10m/s2 downward in what I'll call here the -y direction, then the effective gravitational constant for the cup and you is This means gravity now feels as if it is pointing downward and toward the rear of the vehicle. The angle is or roughly 27o toward the rear of the car from downward. It stands to reason that it would slide off the dashboard since effectively gravity is pulling it not downward, but 27 degrees rearward. Assuming the friction between the cup and dashboard isn't very big, it slides.

Accelerating Train

Have you ever tried standing on a train without holding on while it accelerates away from a station or slows for an upcoming station? If you have, or if you could imagine it anyway, you need to lean in the direction of the acceleration a bit. That's because of the exact same reason. If the train is accelerating away from a station as it gets up to speed at the rate of the previous example (not likely in a train), you'd need to lean forward 27 degrees to stay balanced. If you dropped something from your hand in that train, it'd fall backward and downward at a 27 degree angle with respect to vertical. The rate of acceleration of your keys from your hand would be In other words, gravity is effectively downward and backward now instead of just downward as it is in a non-accelerating train.

ISS Astronauts

Even without knowing any physics about orbits, there's one thing you can know for certain. Since earth's gravity pulls all things toward earth's center, and since at the location of the International Space Station (ISS) gravity is 89% as strong as it is here, and since they are clearly experiencing zero gravity, they must be accelerating directly toward the center of the earth at 89% of 9.8m/s2=8.7m/s2. This must be true since the effective gravitation is zero. This implies that the downward gravitational field must be cancelled by an equal downward (centripetal) acceleration.

How this is possible in a sustained fashion is that they are undergoing centripetal acceleration while in orbit. While centripetal acceleration is directed toward the center of the circular path, recall that such motion nonetheless does not result in getting any closer to the center of the path. So in a very real sense, to orbit means to continually be in free-fall while never getting any closer to earth! If this sounds crazy, it is not just a clever way to spin words together. It is fact. To be in free-fall means to accelerate toward earth at a rate of and that is exactly what they are doing. It is centripetal acceleration.

If it helps, recall that a car going around a circular path is forever accelerating toward the center of that path without ever getting any closer to that center. This is identical.

If the free-fall sensation is what you're after and you can't afford to go to space, there is an option aboard an aircraft. It's common in flight training and for fun for an airplane to be set into a zero-g maneuver. The flight trajectory must be carefully chosen to get it right. What do you suppose that trajectory should look like? Think back to previous chapters and consider what the path of an object looks like when subject to gravity alone (so that it accelerates downward at

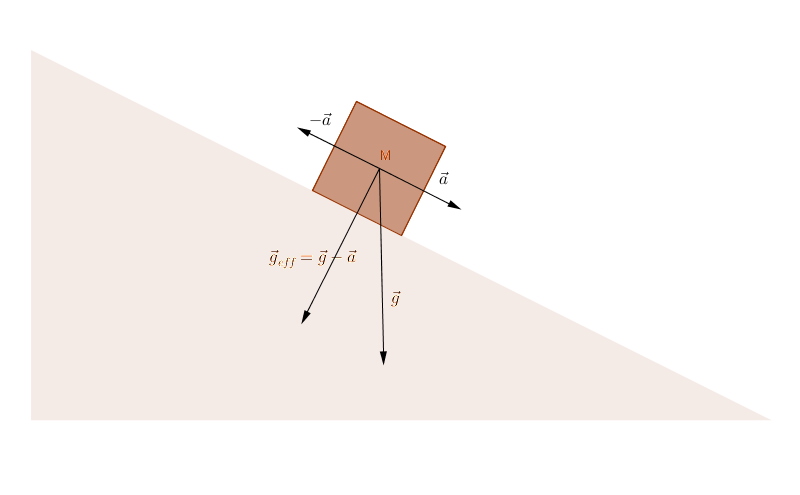

Skating Down a Ramp

If you ever try skateboarding down an incline you'll notice that you have to stand perpendicular to the incline to keep your balance. In other words you certainly do not remain vertical if you want to stay on the skateboard for long. Why is this? Look at the diagram below. When the acceleration is down the incline at a rate the direction of is perpendicular to the incline. That's the way gravity seems to be pulling you as you skate down a hill, and is also the direction your phone will fall out of your hand relative to you if you drop it while filming yourself skating down the hill.

![[url=https://pixabay.com/en/centrifuge-laboratory-research-1049579/]"Laboratory Centrifuge"[/url] by scotth23 is in the [url=https://wiki.creativecommons.org/Public_domain]Public Domain

[/url]](https://www.geogebra.org/resource/gmbccpTt/Sc2aeZ8w3KosHgB2/material-gmbccpTt.png)

Centrifugal (not Centripetal) Force

In this centrifuge a technician places test tubes. Each of the tube holders sits vertically when at rest, but as the centrifuge rotates, the individual buckets holding the tubes swing outward on pivots. At very high rotation rates the tops of the test tubes will all be facing the center of the centrifuge because the outside edge will effectively be "down" to them.

Many physics textbooks make a strong statement about the virtual (not real) nature of the centrifugal force, which is the one makes these test tubes swing outward, or the one that you feel pushes you outward as you round a corner in a car. These books tell you that the centrifugal force doesn't actually exist.

While it's true that in the coordinate system of the road the centrifugal force doesn't exist, in your accelerated reference frame (inside the car) it is very real and is in fact indistinguishable from a new source of gravity! I maintain that it is real because you can measure it with accelerometers or force probes or any of the tools commonly used in physics labs.

Why do you feel pushed toward the right side of a car when it turns left? Based on our previous studies, in the non-accelerated refernce frame of the earth, your centripetal acceleration is directed toward the center of the circular path (left) and is given by The argument in that reference frame is that your body wants to go in a straight line (Newton's first law) and the car beneath you is turning left. This makes you strike the right side of the car. But we don't experience that from a non-accelerated reference frame as an outsider to our own lives. From our vantage point inside the car it feels like some new form of gravity is pulling us rightward.

The effective gravity that you feel while being inside the accelerating car is made up of the opposite of the centripetal acceleration vector above plus earth's gravitational field, or Inside the car where you feel this, things do in fact slide to the outside of the car because gravity effectively acquires an additional outward radial component.

This principle is used to design centrifuges, or rotating devices used to separate fluids based on density. In a cup resting on a table, the denser fluids eventually find their way to the bottom of a cup - as when you mix oil and water. However, if the fluids don't flow very quickly or if there is only a subtle difference in density then we'd need stronger gravity to cause them to separate. With the goal of making stronger gravity in mind, such fluids are placed in rapidly spinning vessels and can experience hundreds or thousands of times earth's gravity toward the outside of the spinning centrifuge. The densest materials end up on the outside edge and the least dense closest to the center. When the test tubes stop spinning, the densest parts of the mixture end up on the bottom with the least dense on the top.

Lean Angle

When you ride a bicycle or a motorcycle, to stay balanced means to keep the contact patch, which is where the rubber meets the road, directly beneath your center of mass. However, when rounding a turn you must lean. As the rider, there is a clear sensation of being pushed outward by the centrifugal force. This is because to the rider there is a component of effective gravity pointing outward that has a magnitude exactly equal to the centripetal force, but in the opposite direction.

How then should we find the required lean angle for a given turn? Simple! Effective gravity tells us which way is 'down'. The wheels need to be under you in that direction. Look at the diagram below. From the angle we can easily see the connection between gravity, the centripetal acceleration and the lean angle.

Lean Angle. "Supermoto" by Timo Budarz is in the Public Domain, CC0 / A derivative from the original work

Knowing the lean angle doesn't tell us how fast the rider is going since there are two unknowns - both the speed and the radius of the turn. We need to know one or the other to do the math. Suppose we know the track design and know that the rider is going around a turn of radius 40m. How fast is he riding? Do the trig, assume g=10m/s2 for simplicity, and see what you get.

What is the speed of the rider?

A Historical Aside: Einstein and Gravity

Einstein's primary thought that is said to have led him to the theory of general relativity was exactly the material of this chapter. He was struck by the inability to distinguish acceleration from gravity. He followed that thought to all of its logical conclusions and changed the world by discovering the structure of space-time.

He found that our universe is a curved space and made predictions that showed that his idea of gravity and not Newton's, is actually correct. He found that gravity affects the rate of passage of time, and that acceleration does as well, since they can't be distinguished. Consider how sad it would have been had Einstein quickly concluded that the centrifugal force doesn't exist, that accelerated reference frames are not worth considering, and just moved on!